Many years ago, when I was still in possession of my hair, I entered a subcontract to develop a system to replace paper-based case files for a quango in South Africa.

The main contract was held by a large development shop that specialised in a related, but different field. They had given one of their systems analysts the task of analysing the system (duh!) but had no spare capacity to code it, so they farmed it out to me.

Lots of people tell you how to do things properly. Here are some things I’ve inherited in our Ansible that break things in horrible ways.

Coupling is (roughly) how interconnected different components of a system are. One of the most common patterns in modern software engineering is loose coupling.

The idea of separating things across an API so that you can change things behind the API without having to change other components is very powerful.

I am a great fan of the DBRE book, and an avid follower of the authors’ podcasts, videos and blog posts.

But there is one glaring omission that I can’t find discussed properly anywhere: upgrades.

You need to patch to fix bugs or address vulnerabilities. You need to upgrade for support and new features that developers want.

I understand that site-specific needs make it hard to proclaim detailed edicts. But the DBRE book isn’t about detailed edicts. It’s about principles and a way of working.

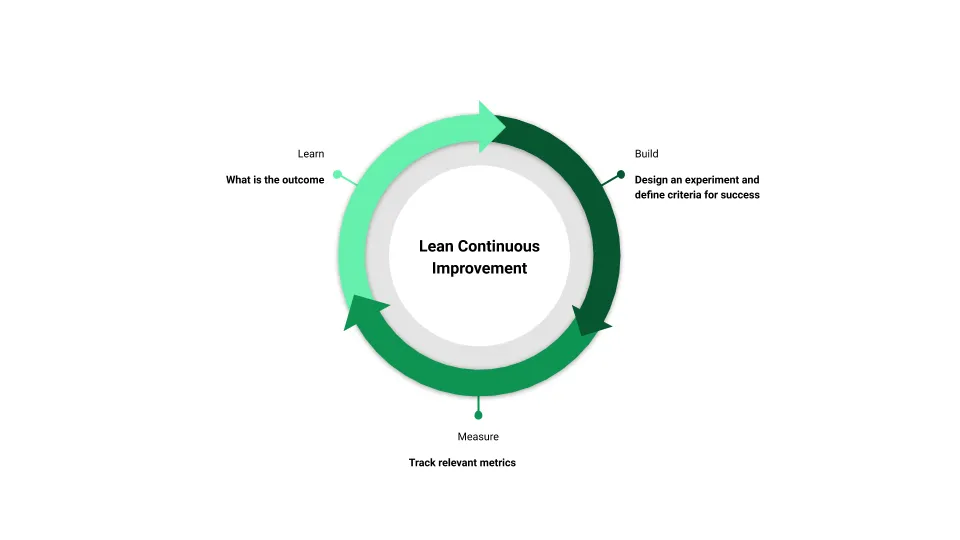

The lean model for continuous improvement looks something like this:

Where you start is a matter of some debate, as is the direction of flow. However, most people start with the idea of building a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) as an experiment; measuring the results; and then learning from the measures they recorded, which then feeds into the next build of the product.

What is an MVP for a Database Reliability Engineer (DBRE)? A good, old-fashioned manual install. A best practices manual install.